The Birth Plan: What It Isn't

Posted on

Last week, I saw a comment on a public facebook post. The post was asking for experiences of hypnobirthing, and the comment said, “my advice is to write your birth plan, and then have a ceremonial burning of it, because that’s the only part of your plan that will actually happen”.

I felt sad.

Sad, because the commenter will have written a birth plan and then had it ignored, or deviated from at some point during her birth(s). Obviously I don’t know what her birth experience was, and I didn’t ask. However, I have asked other people before, and it’s very common that, upon digging into the reasoning, the experiences, behind a statement like that, you find someone who had control ripped away from them. Someone who has been subjected to inflexible hospital policies, who has felt ignored or unsupported or unhappy, who has been coerced, perhaps been assaulted (whether they realise it or not), who has come out of their birth feeling disappointed, and has then been told or felt that they expected too much because the only valid goal of birth is A HEALTHY BABY.

Sad, because by giving this advice the commenter is perpetuating the negative air around birth, that it is wildly unpredictable, and likely horrible, and if you have a nice birth it’s usually by accident, not by planning it. The way some people deal with the trauma of feeling like they had no control over their birth, is by actively relinquishing control to others in the future. It is a protective mechanism, designed to prevent future harm. And by encouraging others to do the same those people are protected too. It is compassionately meant, but it gives the impression that a positive birth is only achievable if you’re lucky, and most people aren’t so, y’know, brace yourself.

Sad, because it doesn’t have to be this way. Birth doesn’t have to be like that, and birth plans get an undeserved bad rep. They’re pretty important, but we have to make sure we’re using them correctly. And using them correctly means thinking about them correctly.

The word plan has a lot of assumptions and definitions linked to it. Like a word association game, when someone says plan, it brings to mind timetables, flowcharts, detailed designs, end goals and the list of steps required to get you there. It’s not bad that those things spring to mind – that is how we store information in our brains. We form little clusters of knowledge based on our previous experiences. They’re called schemas, and they’re like folders in a drawer in a filing cabinet. They include all sorts of bits of information like appearance, behaviour, texture, colour, sounds, how we relate to whatever it is, what it can be used for, where we might encounter it, etc.

The reason babies misidentify things when they are very young – why, at first, every 4 legged animal is a cat – is because their schemas are pretty basic and lack refinement. A creature walks into the room, Muma says it’s a cat, this cat has 4 legs and fur, therefore the creature at Aunty Sophie’s house that also has 4 legs and fur must also be a cat. Later on, the information about fur texture and barking/meowing and movement and behaviour are added, and the child splits the original folder into two individual ones, one for the ‘cat’ at home and one for the ‘dog’ at Aunty Sophie’s. The two stay close to each other, in the same drawer, because there are plenty of overlaps: has fur, is a mammal, can be kept as a pet, etc. Other drawers might have reptiles and birds and fish in, but they’re all in the same cabinet because they’re all animals, and then there are multiple separate filing cabinets for all the other things we know about like bike riding or wall building or writing essays.

It’s a pretty efficient way of storing knowledge, and it allows us to instantaneously access a vast amount of information about a thing as soon as we see it, based on our previous experiences. The problem is that that by forming those schemas, we can add information to the schema that is incorrect, or only applicable to the odd example, or is a personal judgement. We then rely upon all that information as though it’s factual and applicable to the entire schema. It’s how stereotypes are formed, and how they become damaging. We can also try to put something into a schema that it doesn’t actually fit into all that well, which means we are then making assumptions about it that are wrong. And that is where birth plans come in.

At first, most people don’t have a separate schema for ‘birth plan’ – they lack the personal experience so they haven’t developed one yet. When you don’t have a separate schema for ‘birth plan’ you go to the nearest one that works (even if it doesn’t fit quite right): ‘plan’. Therefore, if your schema for ‘plan’ is something fairly fixed, with defined things happening at certain times and expectations that things will happen exactly as you intended, then you will apply that reasoning to a ‘birth plan’. But if you see a ‘plan’ as being flexible, with contingencies and allowances for things to pan out differently, then you will see a ‘birth plan’ as being that way too. It is also affected by how other people conceptualise ‘plan’. More than once I have found clients reluctant to make a birth plan because it feels too prescriptive and inflexible – they are using information from their ‘plan’ schema that says that that is what plans are like. Or they say it’s pointless because they don’t have any experience yet.

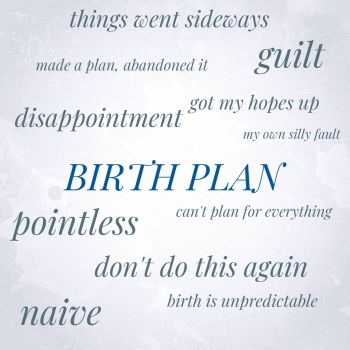

Birth plans can also be especially difficult to write when things have not “gone to plan” before – they feel like tempting fate, or like they’re pointless. Why get your hopes up for a lovely birth when you’ve got firsthand experience of how lovely births can fly out of the window? ‘Birth plan’ now has its own schema, which includes imported information about plans in general, and has a disappointing personal experience and various judgements attached to it.

We can change how we feel about a birth plan by changing how we see plans in general – by seeing them as fluid and adaptable to change – and by doing our best to avoid the judgements that we are so good at making, especially if it involves putting something onto ourselves as mothers.

What a birth plan isn’t

It isn’t set in stone. Birth plans aren’t rigid and dedicated to following a single path, because birth isn’t rigid, and the possible pathways it can follow are numerous. A birth isn’t a construction project with an hourly schedule, that would mean massive additional expense if facing inclement weather or delays in sourcing materials. A birth plan doesn’t set the expectation that birth will be One Thing, and this is the only path to that One Thing.

It isn’t naive. Making a birth plan doesn’t show a lack of understanding about how birth can go. We all know birth is unpredictable. It isn’t naive to want the best birth experience you can have, while understanding that the process may unfold in a multitude of different ways. It isn’t naive to want to come out of birth not traumatised – I would argue that that is, in fact, a bare minimum that one should expect from one’s birth. It isn’t naive to be hopeful.

It isn’t a sign of someone putting themselves above their baby. This is a bugbear of many doulas – the assumption that wanting to have a positive birth experience must mean you want that experience at the expense of your baby. Like it isn’t possible to want more than one thing at once? Like a healthy baby and a good experience are mutually exclusive? Human beings are complex creatures; we can want two things at the same time. Indeed, we are so complex that we can want multiple things at the same time, even the things that genuinely ARE mutually exclusive! And a positive birth AND a healthy baby are very much NOT mutually exclusive.

It isn’t pointless. The process of making a birth plan is an important one because you learn so much while you’re making it, and learning more is rarely a bad thing. Even if you are faced with a scenario you never could have predicted, there are many things in your plan that are transferrable. And even in the most unexpected of situations, there are always a few basic things that are important – respect, dignity, feeling safe, not feeling alone.

In the next part I will talk about what a birth plan is, as opposed to what it isn't. In the meantime, are there any things you would add to this list?

Add a comment: